New Exhibit at the Blanton Will Have You Feeling the Bern

13 julio, 2020Economic exploitation. Class and racial disparities. A need for radical change. This isn’t a recap from the most recent Democratic debate; it’s what helped spark a social movement in Latin America during the 1920s and still reverberates today. «The Avant-garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s» at UT’s Blanton Museum of Art is a robust exhibition documenting a short-lived yet action-packed leftist ideological era that served to empower the non-elites of the day, from peasant to professor. Modernization, it turns out, is an old idea.

The exhibition, which previously traveled to Madrid, Lima, and Mexico City, is now on its tour’s final leg here in Austin. The sizeable catalog that accompanies the show – which features over 200 works – serves to contextualize the movement’s many cultural complexities, international influences, and ideological contradictions. Centered around the publication Amauta, a proto-«alt zine» published in Peru between 1926 and 1930, the exhibition covers politics as much as poetry, pre-Colombian art as well as postcolonial essays. Paintings feature as prominently as pamphlets.

Amauta was started by the writer, activist, and «self-taught» Marxist José Carlos Mariátegui, who was born in Southern Peru and raised in Lima. At a young age, he contemplated the priesthood before turning his attention to journalism, writing for increasingly left-wing newspapers until he decided to start his own: La Razón. But his radical venture went too far for the ruling government at the time; Mariátegui quickly headed to Europe, where he traveled through avant-garde art circles in Germany, France, and Austria before settling in Italy. Upon returning to Peru three years later, the twentysomething began interacting with various figures in the intelligentsia.

Energized by his exposure to European modern art and literature, he continued honing his leftist interests in politics and culture. By the time he began publishing Amauta (Quechua for «wise one,» in reference to the ancient Inca nobility), Mariátegui had amassed a large network of artists, intellectuals, and writers to take part in his publication, creating a veritable salon without walls – an early form of social media.

The exhibition begins with an oil painting of Mariátegui by the Argentine artist Emilio Pettoruti, whom he had befriended while in Italy. It is a logical starting point, a portrait of the activist as a young man, just as his brief yet blazing career began. (Mariátegui died less than 10 years later, in April 1930 at the age of 35, due to health complications from a childhood leg injury.)

Despite his encounters with European avant-gardism and keen interest in classical Marxism, Mariátegui returned to Peru with a desire to explore these ideas within the context of his own society. He chose to break from those Eurocentric influences in order to stoke a regional and, more broadly, Latin American conversation. Peruvian expats in Havana, Mexico City, and Buenos Aires helped to expand the social movement in those regions; and though the movement remained unnamed, its collective energy became unmistakable. Amauta offered an intellectual and cultural forum for a multitude of -isms: socialism, anti-imperialism, Indigenism.

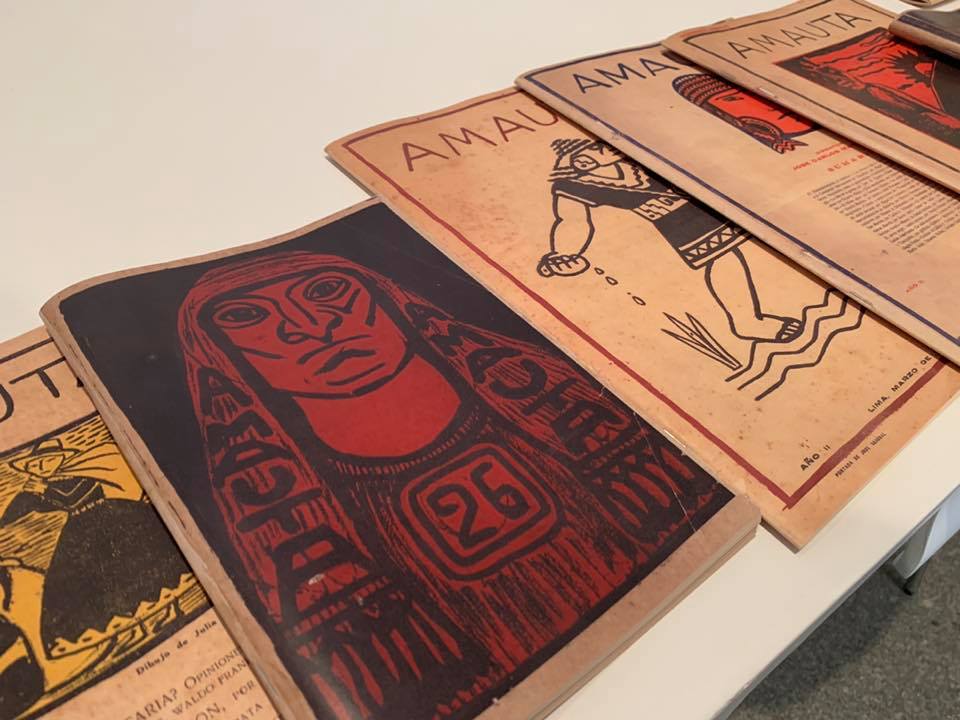

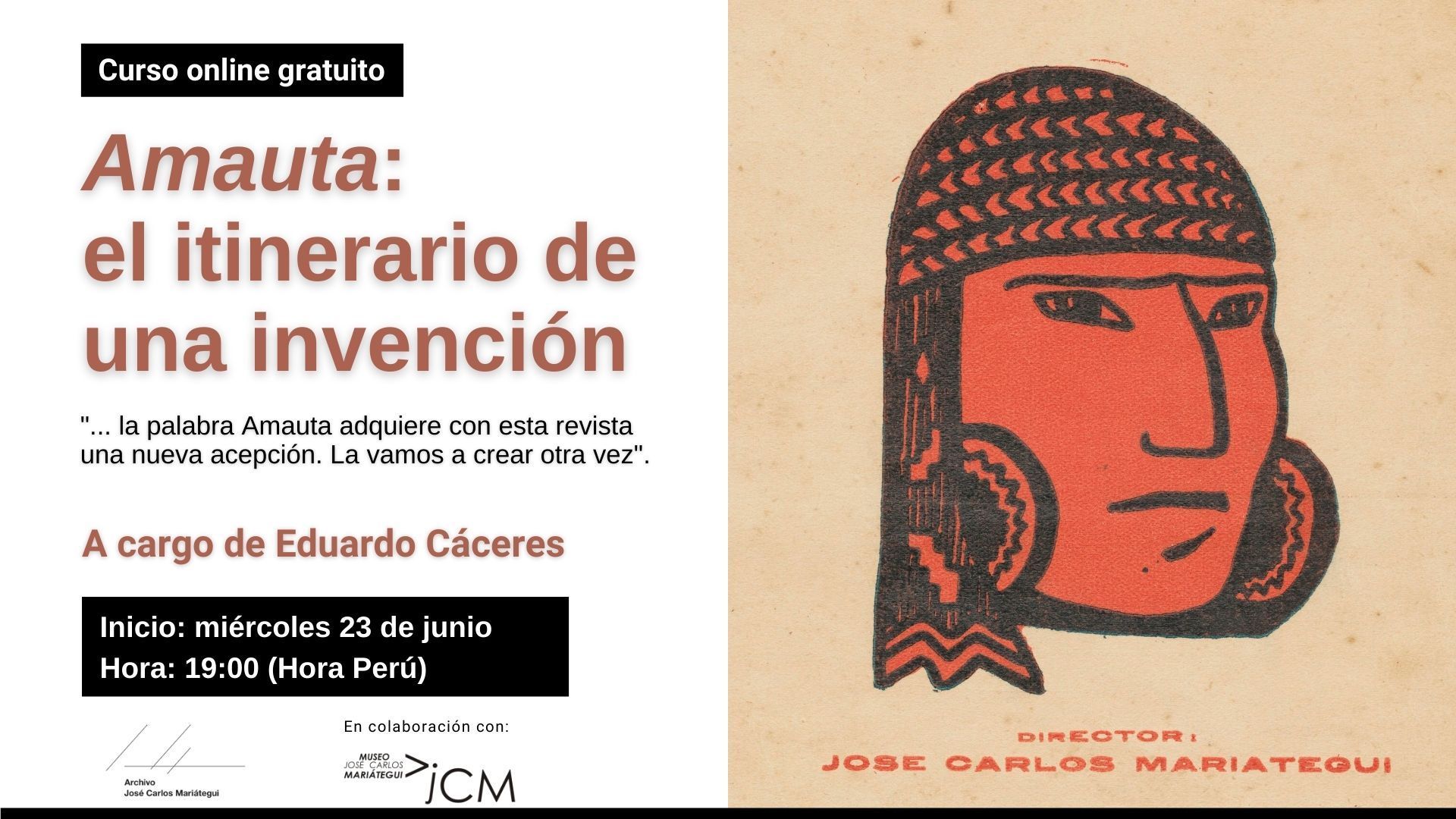

Not to mention art. Artist José Sabogal oversaw the journal’s graphic program and designed many of its cover images, including the one for the first issue in September 1926: a red and black woodblock print of an elder in traditional garb. The strong image paid homage to both the ancient Incan empire and the role of the marginalized Indian in contemporary Peruvian society. Such woodblock images served to reinforce aesthetic notions of primitivism and the perils of modern society, the labor-intensive nature of hand carving in stark contrast with the impersonal swiftness of mechanical production. From the magazine’s inception, Indigenism and activism were woven together with socialism and modernism, as complex and detailed as an Andean Indian wall tapestry.

The exhibition features both Indigenous objects such as textiles and earthenware, and modern art – paintings inspired by cubism and futurism – further illustrating the multi-disciplinary complexity of Amauta. An ornate red cedarwood door carved by university students under the tutelage of designer Gabriel Fernández Ledesma and sculptor Guillermo Ruiz, for instance, hangs impressively in one gallery as an important symbol of traditional artisans’ work, much like those woodblock prints so heavily dominating the magazine’s graphics. (Italian artist and activist Tina Modotti photographed the door for the magazine’s 20th issue.)

In the final part of the show, glass encasements displaying journalistic and printed materials of the day speak to the movement’s strong political pulse. At the heart of it is a first-edition copy of Seven Interpretive Essays of Peruvian Reality, featuring Julia Codesido’s Incan-inspired original cover art. Published in 1928 and widely regarded as Mariátegui’s Marxist masterpiece, the collection addresses such issues as the economy, modernization, and the plight of the oppressed, particularly the «problem of the Indian.»

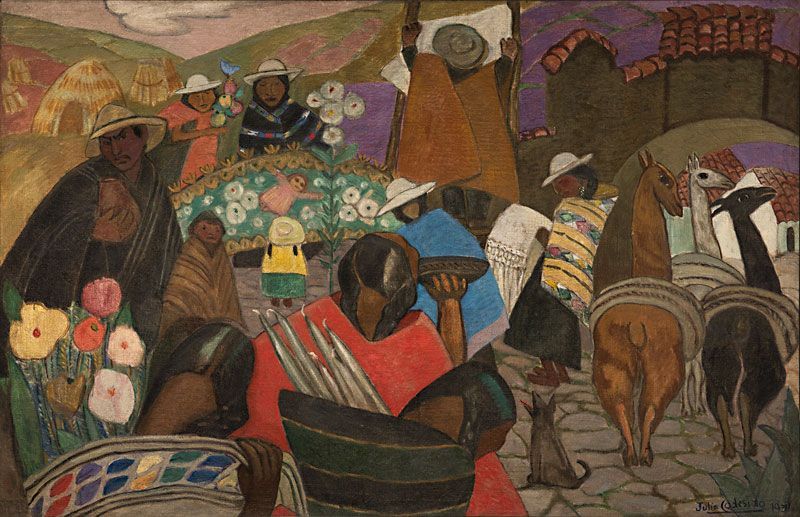

Codesido’s oil painting Mercado indígena (1931), produced a year after Mariátegui’s death, serves as a poetic end note for both the exhibition and the kinetic era brought on by Amauta. The painting depicts a vibrant village scene with figures dressed in traditional Andean clothing at a local market, buying and selling flowers as well as various handmade crafts. There is a joy and dignity on their faces, adults and children alike – even the donkeys and barking dog appear happy to be there. The scene conveys an idyllic Peruvian existence, clearly made better by Amauta‘s brief but intense impact. It’s a celebration of what Karl Marx referred to as «species-being» or human fulfillment – a revolutionary vision shared by José Carlos Mariátegui.

«The Avant-garde Networks of Amauta: Argentina, Mexico, and Peru in the 1920s» is a fascinating examination of a social movement that has echoed across a century, perhaps to our own upcoming election. A once palpable momentum once again seeking revolutionary change. This time, in the form of a democratic socialist who might just be our country’s next president.